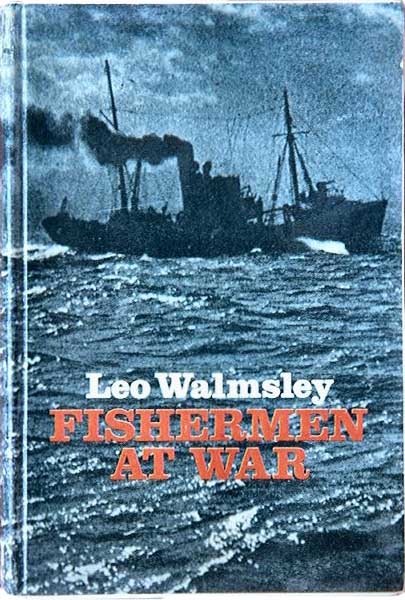

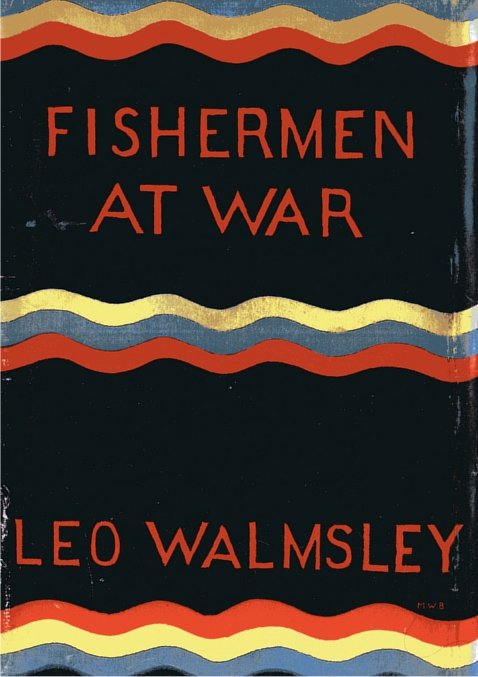

Fishermen at WarIs it an underrated masterpiece?A review by Halifax member Graham HigsonAs Leo Walmsley and his young family sheltered in the idyllic landscape at Leith Rigg, it was difficult to believe there was a war. But, as he tells us in The Golden Waterwheel, there was no mistaking the occasional drone of the British warplanes, nor the sight of naval patrol vessels passing along the coast and quite visible from his house. The Americans, however, didn't believe there was a problem here. To them, the Second World War was merely some kind of token hostility that couldn't possibly concern them. And so it was through his agent that Leo was offered the commission to write a book for an American publisher who had strong British sympathies – a book that would describe the conditions facing the plight of those working in the North Sea. The idea, of course, was that the book should illustrate that this was no "phoney war", and he was asked for "the truth, the ungarnished facts". In other words, pro-British propaganda. The result, Fishermen at War, was published in 1941 and presumably

filled the American publisher's requirements. It seems sad, though, that

But how well is this masterpiece rated amongst the members? It rarely gets any mention in the Journal and I can't help but get the impression that it ranks fairly low on people's reading list. This prompts the question – do we fully appreciate the value of such a work? Does the title do it justice and induce an image of the rare narrative contained within? Bearing in mind that most books about the war have been written in retrospect, they tend to be like those Sunday afternoon war films that were on the telly when I was a kid. You know the ones I mean, where the true horrors of the situation have been somewhat played down – censored, even, almost as if the makers were unable to come to terms with the absolute horror of armed conflict. Because Leo began writing it during the winter of 1940, whilst hostilities were being committed, Fishermen at War has an acuteness and immediacy that places the reader firmly there amidst the action. But don't make the mistake of assuming that this is purely a textbook: Leo was, after all, an accomplished communicator. What he does here isn't at all dissimilar to his treatment in British Ports and Harbours in which, although ostensibly a piece of non-fictional prose, he immediately draws us into the narrative, taking us into his confidence, giving us a front seat and making his experiences ours also. In Fishermen at War there is no plot as such: Leo begins by reflecting on the horrors of The Great War, then describes that although his own farm seems remote from the current conflict, the people in nearby Whitby (note: not "Burnharbour"), are beginning to find conditions difficult. This he does by reintroducing some old friends . . . The Lunns had featured prominently in the Bramblewick trilogy and, in

Fishermen at War, we are reacquainted. Leo has brought these characters

literally into our lives, so much so that they are a part of us, such was

his skill. This book serves as a fitting sequel to Sally Lunn,

Whilst at the Lunn's house in Whitby, Leo asks how the war is affecting them. Henry's comment, "I don't think they will fight mucky in this one", is answered later when, out on their keeler, they come under close scrutiny by a German Dornier. Leo's first-hand account of the fear of being attacked is the first of a collection of anecdotes describing the merciless gunning of unarmed fishing vessels by bandit enemy aircraft. Now it goes without saying that Leo already had enormous respect for the courage and bravery of the fishermen, even in peacetime. But in this book, we can do no other than share his admiration for the fearless way in which they continued to fish against a new and, this time, thoroughly evil adversary. With the co-operation of the Admiralty, he is given the opportunity to visit a number of East Coast ports and interview the crews of the naval patrol vessels and trawlers that are engaged in the hazardous minesweeping operation. Many of the personnel recount their tales of horror being attacked by an enemy "who wasn't playing fair". He speaks with sailors, naval officers and fishermen who have been hurriedly trained for minesweeping service – all of whom serve to present a valid three-dimensional picture. Other sections describe the eventual conquering of the threat posed by the new magnetic mine that was designed to detonate when in the presence of a steel hull, and the story of an heroic rescue by the Whitby lifeboat. The climax of the book involves the word-by-word account of the Dunkirk evacuation as told by a young Whitby man. This is indeed a rare insight into the horrors as they affected real

people. No amount of visual drama could present this quality of detail or

Leo ends it with the words, "And, not because I wished to show to what depths of conduct the human tools of Nazism can fall, but to what heights of bravery and fortitude and self-sacrifice and kindness men can rise, I have written this book about the British fishermen believing that their qualities are not exclusive to our race, but symbolise the good in mankind, which in this fight must inevitably triumph." Now that's a book worth reading – a superb example of social history, and one by an author whom I would love to have met. Back to Book reviews |

|

Copyright © 2013 The Walmsley Society | All Rights Reserved

|

with even

a photograph of Henry at the beginning. If nothing else, we are able to

renew what has become a personal friendship with this family. But this is

merely the icing on the cake: what follows is the stuff that should define

the book as a valuable historical document.

with even

a photograph of Henry at the beginning. If nothing else, we are able to

renew what has become a personal friendship with this family. But this is

merely the icing on the cake: what follows is the stuff that should define

the book as a valuable historical document.